Your favorite foods take a wild ride after you take a bite. Picture a go-to snack and consider its journey through your digestive system. Take a ripe, juicy apple, for example. The fruit is full of nutrients for your body to use.

But how does that fruit become usable in your body? After all, your blood isn’t pumping microscopic apples through your arteries and veins. Your body is utilizing the chemical compounds that make apples crunchy and sweet.

Those compounds are extracted from your food through the digestive process. It’s the method by which your diet’s fats, sugars, proteins, fiber, and essential vitamins and minerals—as well as other important nutrients—find their way out of the food you eat to power your body. Digestion also removes waste. And this process is constantly going on in your body.

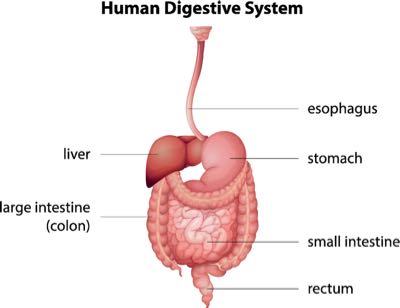

From dinner plate to elimination, the food you eat takes a long trip through your digestive system. Take a look at the path your food will follow as it is digested:

Mouth >> Esophagus >> Stomach >> Small Intestine >> Large Intestine

At each step along the digestive journey, food is modified and broken down into usable pieces. By modeling this system step-by-step, you can gain a better understanding of the fate of your food after it enters your body.

Before exploring the ins and outs of the digestive system, let’s brush up on the vocabulary. Knowing the words associated with the digestive process will make learning about it a piece of cake.

Eating is by far the most enjoyable part of the digestive process. Your mouth and tongue encounter foods and beverages of all varieties, textures, and tastes. And together, they begin digestion by breaking up the food you eat into small, easy-to-swallow pieces.

You may think digestion begins the moment you take a bite. But in some case, it starts even before that. The sight, smell, or thought of food can be enough to trigger your salivary reflex. That’s why your mouth waters when you’re hungry. Saliva is also produced with the chewing motion. It moistens and lubricates food, making it easier to swallow.

Think of the apple. In the afternoon, when you need something to tide you over until the evening meal, an apple is a great choice. Just thinking of the crunchy fruit and the sweet, tangy, juice can make your mouth water.

The salivary glands in your mouth secrete saliva, which is rich in the digestive enzyme amylase. Salivary amylase breaks apart starches into two-chain sugars called maltose. This simple sugar will later be broken down further into single glucose molecules that can be used as cellular energy.

The movement of the tongue is also important in the digestive process. After food is chewed up and mixed with saliva, it’s ready to be swallowed. Your tongue molds and mashes food into a bolus and guides it to the back of your throat. As you swallow, the bolus of food is pushed through the pharynx and into the esophagus.

Digestive Tract Fact #1 – The salivary glands in your mouth secrete between one and one-and-one-half liters of saliva every day.

Boluses of food are shuttled from the mouth to the stomach via the esophagus. This key connector is guarded by two sphincters at the upper and lower ends. These round muscles act like purse strings that open and close as you swallow.

Each sphincter works independently. The upper esophageal sphincter ushers in boluses from the pharynx. The lower esophageal sphincter empties the contents of the esophagus into your stomach. It can also open to release gas build-up from the stomach. This causes you to belch.

The force that propels food and drink through the esophagus is called peristalsis. The smooth muscles that line the esophagus undergo regular contractions after a bolus is swallowed. The wave-like movement created by peristalsis continues throughout the digestive tract. The motion pushes food through all phases of digestion, in the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine.

Gravity can also aid in moving a meal through your esophagus. By sitting upright, the food you eat can travel swiftly and comfortably down the esophagus and into your stomach.

Digestive Tract Fact #2 – It takes only eight seconds for a bolus of food to travel from the pharynx, through the esophagus, and into the stomach.

As you bite, chew, and swallow, boluses of food are dropped into your stomach. The stomach acts as a storage unit that accepts small packages of food over the course of a meal. A large quantity of food can be quickly stored and then digested over a long period of time.

This is remarkable because, when empty, an adult stomach has a capacity of 75 milliliters. But it can stretch and house up to one liter of food over the course of a meal. That’s over 10 times the starting capacity.

Let’s say you decide to eat more than just an apple. Instead you have yogurt, a turkey sandwich, and some carrots, too. That is a lot of food for your body to store in one sitting. Since your stomach is designed to accommodate full meals, you don’t need to worry about bursting at the seams. Your tummy will take each bite in stride, and process the full meal over the next several hours.

The stomach is a dynamic organ, too. It churns, squeezes, and grinds boluses of food and mixes them with gastric secretions. Peristalsis continues in the stomach and is the driving force for blending food with stomach acid. Stomach secretions help make nutrients available for absorption later in the small intestine.

This digestive juice is powerful hydrochloric acid. It’s strong enough to break apart tightly bound proteins into polypeptide chains (smaller chains of amino acids). It can also eliminate potentially harmful bacteria that may be present in some foods.

Since stomach acid is so potent, its production needs careful supervision. At the start of a meal, gastric function is just starting to warm up and very little stomach acid is secreted. Peristalsis gently begins stretching and squishing the stomach in preparation for incoming food.

In the middle of a meal, peristalsis and stomach acid rev up. Gastric secretions are at an all-time high mid-meal. The muscular stomach is rapidly mixing food and drink with hydrochloric acid. This ensures plenty of fluid in which to break down each bite of food. After food is liquified, it is referred to as chyme.

Peristalsis helps pump chyme into the small intestine while you eat. Once your meal is over, stomach acid secretion comes to a halt. But there may be excess acid. When too much gastric juice remains in the stomach after a meal, irritation of the stomach lining can occur. To protect itself, the stomach adjusts acid production to stay healthy and keep you comfortable.

Stomach contractions continue until all the chyme from the previous meal has entered the small intestine.

Digestive Tract Fact #3 – Stomach rumbles are produced by peristaltic contractions as they move contents through the intestinal tract. They occur during digestion and can continue two hours after the stomach has emptied.

The small intestine plays the most significant role in the digestive process. And it’s anything but small. At 22 feet (seven meters) long, the small intestine’s primary role is nutrient absorption. Along those 22 feet of digestive “pipe,” several forces combine to optimize small-intestine function.

The lumen (center) of the small intestine is covered in tiny, finger-like tentacles called villi. These densely packed hairs give the mucosa (mucous membrane) of the small intestine a velvety appearance and help their function.

Think of villi like a densely packed carpeting, soaking up every usable nutrient in sight. The purpose of these villi is to increase the surface area of the small intestine. As chyme is further digested, nutrients are absorbed through the villi and transported to the blood stream. A larger surface area means more absorptive space.

Let’s go back to that apple. The fruit-and-stomach-secretion cocktail (chyme) enters the small intestine and mixes with water and other digestive juices like bile. Rhythmic stirring of chyme continues the breakdown of sugars, fats, and proteins from the apple or whatever your previous meal was.

Bile is critical in the digestion of fats into free fatty acids. Bile is composed of water, salts, acids, and lipids. It is a medium in which fats and fat-soluble vitamins can dissolve and be carried into the blood stream via the villi.

Bile also contains bilirubin, a yellow-orange pigment released by red blood cells as they break down. Your body can’t metabolize bilirubin on its own, so it relies on bacteria to help out. When the bacteria in your small intestine chow down on bilirubin, they produce a dark material called sterobilin. This by product gives stool it’s notable brown color.

You also get some help breaking down your food. Microbes in your small intestine do a lot of work to help make fatty acids available for later use. They work alongside secretions from the pancreas (called proteases) that help digest proteins. Proteases break apart complex proteins into peptide chains, then further into individual amino acids.

Now, glucose molecules, amino acids, and free fatty acids are available to be absorbed into the blood stream through the villi.

Digestive Tract Fact #4 – It takes four to five hours for the stomach to completely empty into the small intestine after a meal.

At end of the journey through the small intestine, most nutrients from digested food have been absorbed. But not everything you eat is an absorbable nutrient. So, what happens to the parts of your food that your body doesn’t need? In the large intestine, undigested material, excess fluids, and mucus all combine to form stool. (There are many more colorful names for it, but stool is the preferred medical term, and what you’ll see moving forward.)

Stool is the solid waste of the digestive process. Believe it or not, your body doesn’t use every particle of food you ingest. Roughage (fiber) travels through the digestive system relatively intact. This is because the digestive enzymes produced in the body cannot break down fiber.

Your snack from earlier, the apple, is a good example of this. The compounds that make the apple skin tough and give the fruit its characteristic crunch pass right through your digestive system with very little nutrient absorption.

Undigested bits of food and fiber accumulate in the large intestine. This final stop on the digestive journey is full of pockets of tissue called haustra. They give the large intestine its puckered appearance. Haustra can stretch to accommodate large amounts of stool as it prepares to leave the body.

The exit of the large intestine and end of the digestive journey—when solid waste is eliminated—is another sphincter called the anus. But in order for stool to leave the digestive tract, it needs a little momentum.

A bowel movement is necessary for your body to expel stool from the large intestine. Very strong peristaltic contractions (the wave-like movements from earlier in the trip through the digestive tract) move stool toward the exit. This creates feelings of pressure in the region and eventually triggers the defecation reflex.

Solid waste is characteristically brown and stinky. You know that bilirubin gives stool its color, but what causes its odor?

If you guessed bacteria are involved, you’re right.

Microbes that reside in the large intestine make a meal of the leftovers from the small intestine. As they interact with stool, gas is created. The smell associated with stool comes from the gases released during the break down of solid waste by bacteria.

Digestive Tract Fact #5 – Stool can sit in the large intestine for up to 48 hours before it is expelled from the body.

When your digestive system runs smoothly, you feel healthy and comfortable. There are simple ways to keep your tummy in tip top shape.

Let’s start with water.

Ample hydration makes the material in your intestines move easily with each wave of muscle contractions. Drinking plenty of water also helps soften the waste that lurks in your gut. When stool is eventually collected in the rectum, water makes it more comfortable to eliminate.

Fiber also eases digestion.

The complex carbohydrate is bulky and adds weight to stool. Bowel movements are easier to pass when solid waste is heavy. Fiber also absorbs water and softens stool as it travels through the digestive tract. Consider increasing your fiber intake if you notice irregularity in bowel movements. Remember, elimination of solid waste can be different for each person. One study found that normal elimination patterns varied from three times per day to three times per week.

But be careful, adding too much fiber too quickly can have unpleasant consequences. Intestinal gas build-up, bloating, and abdominal discomfort can be the result of ramping up fiber intake too quickly. So, increase the amount of fiber in your diet slowly to maintain intestinal comfort. Look for natural sources of fiber to add to your diet. These include:

Another way to improve digestive health is to take care of the bacteria living in your gut. These microbes do a lot to facilitate healthy digestion. By utilizing probiotics, you can help maintain a healthy balance of intestinal bacteria.

Probiotics support the numbers of helpful microorganisms in your gut. They also aid in nutrient absorption in the small intestine and help break down your food. There is growing evidence to suggest that probiotic supplementation may play a role in supporting immune health, too.

Take a closer look at the digestive system and consider the path your food takes. It is remarkable how your favorite meals are torn apart, liquefied, absorbed, and eventually eliminated by your body. And it’s all to harvest the essential nutrients you need to survive.

So, support your digestive system with lots of water and a high-fiber diet. And make its health (and yours) a priority.

Sydney Sprouse is a freelance science writer based out of Forest Grove, Oregon. She holds a bachelor of science in human biology from Utah State University, where she worked as an undergraduate researcher and writing fellow. Sydney is a lifelong student of science and makes it her goal to translate current scientific research as effectively as possible. She writes with particular interest in human biology, health, and nutrition.