In this introduction to the special issue, we take stock of the impact of the TRIPS agreement on international business in the hyper-globalised world of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. We begin by providing a brief background on TRIPS, putting it in the historical context of international agreements on intellectual property (IP) and then looking at the logic of national patent policies, examining how policies may vary across countries, in theory, and reviewing literature that discusses the factors driving historical variation, in practice. We review the key issues in the domestic politics of implementation as the new rules migrate from the international to national levels. Lastly, we consider the implications of TRIPS for the governance of innovations in industries based on ICT and where ICT has enabled global value chains (GVCs), where the speed and distributed nature of innovation makes IPR simultaneously less effective and more necessary.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Uruguay Round of trade negotiations, which began in 1986 and concluded in 1994 with the signing of the Marrakesh Agreement by all 123 negotiating countries, was notable for numerous reasons, including the formal integration of intellectual property rights into international trade rules. When the World Trade Organization (WTO) was launched in 1995, a product of the Uruguay Round, one of its main pillars would be the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).

TRIPS is not the first international agreement on intellectual property (IP); the Paris Convention (patents), Madrid System (trademarks), and Berne Convention (copyright) have existed since the late 1800s.Yet TRIPS can be understood as marking a fundamental break in a variety of ways. TRIPS is much deeper and more granular, placing external constraints on many more dimensions of national IP policy than previous agreements had. Beyond establishing shared commitments to basic principles, as previous international accords had done, TRIPS, in a detailed set of articles, includes specific prescriptions and proscriptions for national policy. 1 Notwithstanding its title, TRIPS addresses national IP measures regardless of whether these are “trade-related.” TRIPS is also stronger and more binding than previous agreements, as the costs of non-compliance are substantial. Because the inclusion of TRIPS in the WTO means that it is subject to the WTO’s dispute settlement system, which authorizes trade sanctions as a penalty against countries judged to be in violation of its rules, failure to abide by the rules can have economically painful consequences. The establishment of extensive and binding rules on national IP policy marks a shift from “international” to “global” IP governance (Maskus, 2014; Drahos, 1997) and, importantly, a major step toward global harmonization of national policies and practices for establishing and protecting intellectual property rights.

This Special Issue presents papers examining 25 years since TRIPS came into effect, in January 1995. In these two and a half decades, much has changed in the global innovation landscape. Technology trade has flourished and more technology has been transferred to subsidiaries by MNEs (Branstetter et al., 2006). Although IB theories emphasize the role of innovation and technological change in originating and strengthening the competitive advantages of the MNE, IB scholarship has focused mostly on considering IPR regulations as a location advantage/disadvantage (e.g., Ivus, Park & Saggi, 2017), or an institutional factor (e.g., Peng, Ahlstrom, Carraher, & Shi, 2017; Peng, 2013) interacting with MNE strategies. Through this Special Issue, our aim is to champion research analysing the contribution of IP harmonization to processes of technology transfer, policy-making, capability building and challenges to governance. Assessing the TRIPS experience to highlight what has worked well and what has not can offer new insights and lessons.

In this Introduction, we take stock of the impact of TRIPS on international business in the hyper-globalised world of the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. We begin by providing a brief background on TRIPS, putting it in the historical context of international agreements on IP. We then look at the logic of national patent policies, examining how policies may vary across countries, in theory, and reviewing literature that discusses the factors driving historical variation, in practice. The following section discusses the international campaign that produced the TRIPS Agreement and considers key issues in the domestic politics of implementation as the new rules migrate from the international to national levels. We then look more closely at the implications of TRIPS for industries based on ICTs and where governance of GVCs feature prominently. The final section introduces the papers in the Special Issue, placing each of them in the broader debates and themes discussed in this Introduction.

One of the remarkable aspects of TRIPS is how it expanded over time during the course of the Uruguay Round. 2 What was originally advanced as a global accord against counterfeiting after years of negotiation ended up being a comprehensive agreement covering a wide range of IP policies. As the content expanded, the axes of political conflict shifted as well. Although, at the time of the Uruguay Round’s launch, divisions over whether to include IP on the agenda were largely of a “North-South” nature, once this hurdle was cleared, subsequent negotiations on substantive issues revealed “North-North” divisions as well.

This dynamic was notable, for instance, in the area of IP for pharmaceuticals. Many developing countries tried to block the inclusion of IP on the Uruguay Round negotiating agenda, maintaining that IP and trade rules should be kept separate, and having failed to keep IP off the agenda they mobilized their efforts to resist the inclusion of the provision that would require countries to allow patents on pharmaceuticals products. After all, prior to the 1990s, few developing countries did so. Though developing countries lost this fight too, 3 the specifics of this requirement (for example, transition periods and whether this should be done retroactively), and more generally the rules about how countries should treat IP in pharmaceuticals, were produced by extensive negotiations and compromise, not only between North and South, the original antagonists, but also among countries in the North. Most European countries, for example, had only recently (since the late 1970s) begun to allow patents on pharmaceuticals, and they too were grappling with the consequences of this change and were resistant to some of the proposals made by countries where pharmaceutical patenting was longer established (Taubmann & Watal, 2015; Reichman, 2009; Matthews, 2002).

As much as the content of TRIPS expanded during the Uruguay Round, the world’s changes outpaced it. The establishment of the European Common Market in 1993 altered (or reflected on-going shifts in) the political and economic strategies of many European countries, and the balance of power within international organizations. The collapse of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union (as well as that of Yugoslavia), and thus the end of communism and state-planning in most of Central, Eastern, and South-Eastern Europe, meant that a large group of additional countries would now seek to attract foreign investment, participate in international trade, and, more generally, integrate into the global economy. 4 At the same time, many developing countries abandoned industrial planning and policies of import-substituting industrialization, reduced barriers to imports and foreign investment, and also sought greater integration into the global economy. And, of course, China, the world’s most populous country, also underwent a major reorientation of economic strategy in this period; though not a participant in the Uruguay Round negotiations, by the time the WTO was launched in 1995, China, which eventually became a WTO member in 2001, was already emerging as an industrial powerhouse.

The worlds of business and technology were also markedly different by the end of the Uruguay Round than they had been at the start. The spread of new technologies of ICT began to gather steam and ultimately ushered in a new phase in the development of industry and global production largely dominated by increasing fragmentation of production and global value chains (GVCs). For the leading industrial countries strident in their demand for stricter IP protection, the TRIPS provisions had few safeguards for the new technology sectors that were emerging, such as software, AI, and telecommunications. Patent and copyright policies towards the new ICT industries, and their relation to competition policy, remain contentious areas where consensus has yet to evolve. In some sectors marked by globalization of production and the presence of GVCs, TRIPS has been almost redundant and supplanted by standards and cooperative agreements over essential patents as the mode of governance of innovation and appropriability. The emergence of digital commerce created new challenges and forms of conflict that TRIPS was unable to address (Azmeh, Foster, & Echavarri, 2020; Haggart, 2014). International labour mobility has also brought a slew of new issues to consider such as trade secrets and espionage activity. Thus TRIPS, though the most comprehensive international IP agreement, was in some ways born outdated, having to cope with new realities that were unforeseen at the start of – and even during most of – the Uruguay Round.

Standard economic theory as outlined in Scotchmer (2004) argues that optimal (patent) incentive polices will differ when we consider the national or international context. In a domestic context, the optimal patent policy tries to balance benefits that accrue to consumers and producers, mainly by addressing the question: how much monopoly profit should the innovator be allowed in order to maximise the social welfare that society as a whole may derive from a new invention? Phrasing the question in this way recognises that pricing under patenting will be higher due to the implicit monopoly granted by the patent and as such will produce a deadweight loss to society as a whole because of the restriction of output and the higher price borne by consumers (Nordhaus, 1969). As a consequence, economic thinking about patents is also dominated by market share arguments and the societal lack of welfare due to the monopoly granted by patents. Indeed, economic theory since Schumpeter has long recognized that patents (and IP protection, more generally) can have both dynamic effects, by creating incentives for innovation, and static and deadweight losses, by allowing patent-owners to charge monopoly prices. The optimal patent policy tries to balance these two effects, and thus the benefits that accrue to producers of innovations and users of innovations. 5

In establishing national patent systems, three levers are available to the government to strike this delicate balance between producer and social welfare interests. These are the scope of patentability, which defines the boundaries of what types of knowledge are eligible for private ownership; the exemptions to property rights, which define the relative rights of owners versus users; and the duration of patents, which establishes the time when privately owned knowledge enters the public domain. 6 In the paragraphs that follow we briefly discuss each of the three levers, though before doing so it is worth noting simply that the first lever, which affects the establishment of the IPR, is the most important of the three in a gatekeeper sense, as the abilities of owners to exercise such rights and how long they may do so are relevant only in the context of there being a property right.

Regarding “scope,” patents are available for inventions and not available for products of nature, but countries may differ in their determinations of what knowledge fits within each of these categories. More concretely (and less philosophically), countries may declare that certain types of knowledge, even if “inventions,” are nevertheless ineligible for patent protection. As noted above, the area of pharmaceuticals provides an example: new molecules and compounds are “inventions,” but until the late 1970s only a handful of countries allowed pharmaceutical products to obtain patents (Liu & LaCroix, 2015; Shadlen, Sampat, & Kapczynski, 2020).

Related to the scope of patentability is the “breadth” of patents, which regards the number and type of claims that are allowed. Broad patents allow the producer to profit from subtle product differentiation and make it more difficult for potential competitors to “invent around the patent” and enter the market upon achieving such differentiation (Merges & Nelson, 1990). Until the late 1980s Japan stood out among advanced economies for having a patent system that imposed narrow breadth, restricting patents on a single claim (Ordover, 1991). For the most part, patent breadth is determined through office practices and jurisprudence, and not a matter of policy per se.

A second lever concerns exemptions to patent rights. With intellectual property, which is based on non-rivalrous material, consumers and other producers beyond the owners (i.e., “third parties”) typically are allowed more rights to use the privately-owned knowledge than is the case with ordinary property. Patent systems will always have provisions that set out and delimit such rights. Some of these will be established as automatic exemptions that do not depend on permission from the rights-holder or the State, such as research use, or preparing products for commercial launch upon expiration of the patent. Other exemptions, which are non-automatic, require the State to grant permission to private or public actors to use patented knowledge without the owner’s consent, as is the case with a compulsory license. Although pharmaceuticals is the area where we observe the most amount of action with regard to compulsory licensing, as discussed by Ramani and Urias in this SI, other sectors where such exemptions play an important part include semiconductors (chip manufacturers need to experiment with various chips to create their own) and seed producers (they need to experiment with seeds in order to create new hybrids). 7

The final lever of national policies, the duration of patents, is also the clearest: longer-lasting patents allow producers to charge monopoly prices (and thus earn greater profits) for a longer time, while consumers in the economy pay higher prices for longer periods of time. Note, however, that in sectors with rapid technological change, the length of the patent is less consequential than it might seem if inventions become obsolete well before their patents expire.

The discussion of the three levers allows us to conclude that countries’ IP systems afford “stronger” protection when they allow more types of knowledge to be patented, the exemptions to owners’ private rights of exclusion are fewer, and they last longer. Indeed, we could, at least theoretically (subject to data constraints), use these dimensions to compare the strength of all countries’ patent systems across time and space. 8

Having explained how patent policies may differ in theory, the next question is what factors account for variation in practice. Scholars have argued that IP institutions are endogenous to the growth process and acquire prominence with the growth of technological capacity, and strong IPR in earlier stages of development can prove to be barriers to the development of technological capability and innovation, rather than act as incentives. As countries acquire more innovative capabilities and their scientific and industrial sectors expand, and as their firms move closer to the technological frontier, the case for stronger IP protection often follows (Sweet & Eterovic, 2019; Sweet & Maggio, 2015; Kalaycı & Pamukçu, 2014; Acemoglu, Aghion, & Zilibotti, 2006).

Accordingly, a substantial body of research has shown that countries’ choices of how strong to set the level of protection in their IP systems have, historically, been a function of domestic conditions, such as levels of income, industrial structure, and scientific-technological capabilities. In general, countries seeking to catch-up with wealthier and more technologically advanced countries tended to offer weaker IP protection to facilitate the use of foreign knowledge and information, and subsequent strengthening of IP tended to reflect changes in these same characteristics. Indeed, the close relationship between national conditions and IP policies has long been demonstrated (Chen & Puttitanun, 2005; Lerner, 2000; LaCroix & Liu, 2009; Maskus, 2000, 2012; May & Sell, 2006). The Netherlands and Switzerland had no patent systems in the 19 th and much of the 20 th centuries (Schiff, 1971); the German patent system was only established in 1870. And even as countries had patent systems, some areas of knowledge remained off limits, and the rights of exclusion were moderated. In the USA, although a patent system to protect inventions was mandated in the first article of the constitution, throughout much of the 19 th century, protection for inventions originating abroad remained weak (Peng et al., 2017; Mowery, 2010; Khan, 2005). 9 As noted, not until the late 1980s did Japan offer stronger patent protection, rather it was designed to maximize the diffusion of knowledge and maximize opportunities for local actors to develop technological capabilities (Ordover, 1991). For many late-developing countries, IP policies featuring weak patent protection were fundamental to their industrialization strategies (Kim et al., 2012; Odagiri, Goto, Sunami, & Nelson, 2010; Kumar, 2002).

This scenario of national variation in patent policies was a function of a permissive international environment. That is, prior to TRIPS, international rules were based on the principle that different approaches to IP made sense in different countries depending on national conditions. Indeed, international rules on patents, which established a framework for an international patent system (e.g., rules on priority dates) but imposed few substantive obligations on countries, explicitly accommodated cross-national diversity. In the next section, again focusing on patents, we explain the major shift in global governance, from the Paris Convention to TRIPS.

The most important provision of the Paris Convention regards “national treatment,” which requires countries to afford foreign inventors the same opportunities and rights as those available to national inventors. But this is extremely limited. National treatment equalizes treatment at whatever level the country chooses, but it does not address the level of treatment. That is, in the language of the three levers of policy discussed above, national treatment does not say that countries should allow patents over given types of knowledge, or limit exemptions in particular ways, or have longer-lasting patents, but rather that if they do grant patents in particular technological classes, with particular rights of exclusion attached for a given period of time, they must treat foreign inventors the same as they treat national inventors. If a country does not offer strong patent protection, national treatment simply means that no one receives strong patent protection in that country.

From the perspective of firms in information- and knowledge-intensive industries which sought stronger protection on a global scale, the Paris Convention was clearly inadequate. They wanted to raise the bar across the globe, establishing international arrangements that would encourage harmonization at a higher level of IP protection. Starting in the late 1970s and early 1980s, these firms, both on their own and through their sectoral associations, mobilized intensively in the US and Europe to create a new international arrangement, with the key step being to link IP rules to international trade (Sell, 2003, 2010; Ryan, 1998; Drahos, 1995). In doing so, they made achieving stronger IP protection a key feature of American and European foreign economic policy in this period.

The USA first linked IP practices to trade in 1984, with a reform of the Trade Act that defined “unfair” trade to include IP practices that did not meet US standards. The punishments attached to transgressions could range from trade sanctions imposed under Section 301 to withdrawal of preferential market access provided by the General System of Preferences. Then, in 1988, just as the Uruguay Round discussions on IP were picking up pace, the US Trade Act underwent a further amendment, this time creating a new mechanism that was specifically about IP. Starting in 1989, the United States Trade Representative (USTR) began issuing an annual “Special 301” Report, essentially a global report card that evaluated all countries’ IP practices and placed those judged to be problematic on the “Watch List” or “Priority Watch List.” As countries were placed on the Watch List and then escalated to the Priority Watch List, the threat of penalties increased, and when a country was identified as a “Priority Foreign Country,” the USTR was obligated to initiate proceedings to apply sanctions. 10

Not surprisingly, many countries that were most resistant to IP negotiations in the Uruguay Round were targeted directly by the USTR. Unilateral pressures of this sort not only brought many hesitant countries to the negotiating table, but made agreement on a multilateral set of rules more attractive too (Odell, 2006; Drahos, 1995; Bayard & Elliott, 1994; Bhagwati & Patrick, 1990). When the WTO was launched in 1995, the agreement on IP, TRIPS, was included.

TRIPS took international IP rules to an entirely new level, by calling for harmonization at a level closer to what was available in wealthier countries. 11 Its aims extended far beyond reciprocal national treatment of foreign inventions to the harmonization and strengthening of IP systems in the world. In the quest for stronger protection, TRIPS addressed each of the levers of national policy. It called for wider scope, requiring patents to be granted in all fields of technology; it tried to restrict the range of allowable exemptions to patent rights; and it established longer terms for patents, requiring terms of 20 years from the date of application.

This new approach to IP did not respect where particular countries were in their national evolution, but sought to construct a uniform system of protection that could support a global market for trade in technology goods. Low and middle-income countries who were net buyers of technology, were fearful that stronger protection at home would increase profit flows to foreigners. International profit flows depended upon the relative size of domestic markets and the relative sizes of country innovative capacities. Thus, countries with smaller national markets and countries with stronger innovative capacities (most high-income countries) generally favoured stronger protection, but countries with larger markets and weak innovative capacities resisted. Middle and Low-income countries who opposed TRIPS were in the latter group.

It is important to underscore that the WTO was concluded as a “single undertaking,” meaning that all members were subject to all of its agreements. As a result, even countries that resisted TRIPS ended up as parties to – and bound by – it. Thus, once the Uruguay Round was concluded and the new WTO’s rules came into effect in 1995, countries began revising their national laws to come into conformity with TRIPS (and other WTO agreements). In other words, WTO member states moved from a period of TRIPS negotiation to TRIPS implementation (Shadlen, 2017; Deere, 2008). In this context, with participation in the international trading system conditioned on being in compliance with TRIPS, the question that countries faced was not if but how they would comply with the new international agreement.

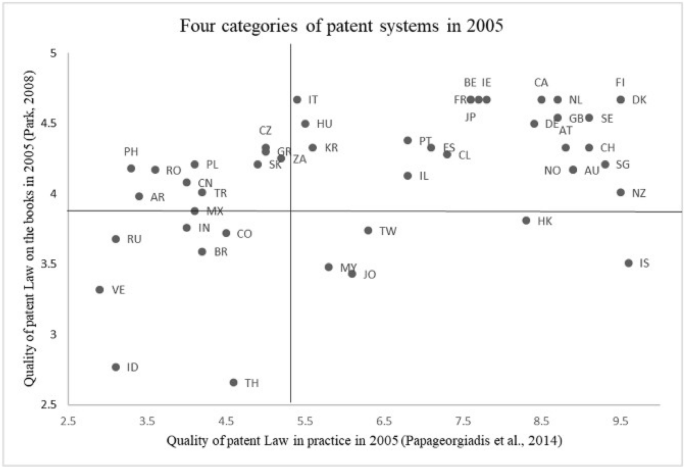

Although TRIPS established harmonization, it did not create a world of uniform patent policies and levels of patent protection. That is, a set of countries could all be in compliance with TRIPS yet all demonstrate differences in the details of their national IP systems. The reasons for this are twofold. First, TRIPS is not a self-executing body of law, but rather an agreement that prescribes and proscribes different practices, leaving matters of implementation to countries. For example, TRIPS establishes a set of conditions that should be met in granting compulsory licenses, but how these conditions are operationalized in national patent systems (What sort of behaviour by patent owners constitute grounds for compulsory licenses? Can the Ministry of Health act on its own? Does there need to be a health emergency, and, if so, how is it determined and who declares it?) was left to be determined locally. This means that TRIPS left countries with policy options (Commission on Intellectual Property Rights, 2002; Correa, 2000), and countries could – and did – comply with TRIPS differently. Second, TRIPS for the most part addressed laws, not so much enforcement practices. That means that not only may countries differ de jure (e.g., the three policy levers, or the details of the compulsory licensing rules), but also de facto due to the enforcement of their new laws. And evidence suggests substantial gaps between de jure and de facto levels of IP protection (Maskus, 2000; Shadlen, Schrank, & Kurtz, 2005). One recent study (Papageorgiadis & McDonald, 2019) shows that de jure IP protection departs significantly from the de facto IP protection for several middle- and low-income countries. Figure 1 is from their paper and shows the two dimensions of de jure and de facto IPR on the two axes. 12

Although attention on lax enforcement has often focussed on China, China is not alone. Figure 1 reveals similar gaps between laws on the books and laws in practice in many other emerging economies, such as Argentina, Mexico, the Philippines, and Turkey, as well as India, Russia and Brazil (many of these countries initially opposed the TRIPS agreement). Indeed, as pointed out in Athreye, Martelli and Piscitello (2020), one can discern two groups of countries – those for whom de jure and de facto IPR move in the same direction (a positive relation) and a smaller group of middle income countries for whom the two are compensatory (a negative relation). 13

As we examine the dynamics of TRIPS implementation at the national level, both introducing and enforcing new laws, it is worth underscoring how the new international agreement altered the nature of domestic politics by imbuing technology-intensive sectors with new authority and importance. This happened in much the same way as Baldwin (2016) argues the reciprocity principle in GATT helped shift political interests to create a juggernaut of tariff cutting behaviour across nations. Prior to TRIPS, national patent policies were shaped largely by strong consumer groups and import substituting industrial sectors. Innovators (actual, fledgling, and aspiring) rarely had large and direct say in the drawing up of national IP policies, which in many developing countries were not designed to encourage innovation so much as to assure that knowledge, information, and technologically-intensive goods were accessible to consumers and as inputs to local industry. By forcing shifts in national policies toward stronger IP protections, TRIPS served as an exogenous shock that changed the distribution of incomes between innovative and non-innovative business groups. 14 Once stronger IP protection was implemented, innovative businesses/sectors gained from the new arrangements while businesses that relied on the previous arrangements experienced shrinking margins and some even left non-innovative lines of business. This changed the balance of political power with the two groups in ways that became self-reinforcing, as in subsequent political conflicts over IP, it was now the more innovation-focused sets of actors in business (and also within the state) that hold the upper hand. And the preferences of actors changed too. Faced with a new status quo, some actors that opposed TRIPS adjusted to the new environment and began to see opportunities where they previously felt only threats. When this happened, they revised their political strategies and were likely to seek alliances with actors that had supported the introduction of new arrangements (Sinha, 2016; Shadlen, 2011).

In the spectrum of goods to which the provision of TRIPS could apply, scholarly attention has focussed sharply on goods with externalities, such as access to medicines and climate change technologies where the stronger monopoly enabled by TRIPS was obviously to the detriment of many poorer nations and poor consumer in richer nations. The adoption of TRIPS, however, came before the full impact of the newly emerging ICTs was felt. Consequently, the ICT sectors themselves and the ICT-mediated global value chains faced challenging governance issues shaped by the uncertainty of IP rights and in some cases, these were sorted out through sectoral innovations in the governance of IP rights.

Improvements in ICTs and rapid globalisation created unprecedented opportunities for the fragmentation of global value chains by reducing the transaction costs of exchanging information and communication across different stages of production. The best example of the changing industrial organization of production is the car industry, which moved from being a monolithic Fordist assembly line to gradual vertical disintegration along component lines. Today the car we drive has engine and components sourced from different parts of the world and includes improvements due to R&D conducted in different countries. Ghemawat (2007) ascribes this development to the globalization of markets being accompanied by the globalization of production. Thus, in many sectors of industrial activity, firms today select the best location for every value chain activity, either at home or abroad, and whether inside or outside organizational boundaries (Alcacer, Cantwell, & Piscitello, 2016).

As ICTs allow higher-quality information to be more readily accessed through a greater diversity of potential channels (Rangan & Sengul, 2009); market-based transactions and outsourcing are favoured and the use of ICT tends to reduce the extent to which facilities are owned by the MNE (Zaheer & Manrakhan, 2001). Thanks to IT-enabled integration capabilities, the fragmentation of processes across units allows firms to exploit complementarities between dispersed fragments, to vary their information-protection approach according to the specific institutional context of each host country, and to (selectively) develop a differentiated use of internal controls over activities performed abroad (Gooris & Peeters, 2016). On the other hand, better quality of IPR institutions in host countries facilitates intra-firm knowledge transmission by MNEs to their affiliates (Branstetter et al., 2006), and shifts the organisational mode towards outsourcing by reducing the need for integration to hedge against knowledge dissipation and opportunistic behaviour by the supplier/local unit.

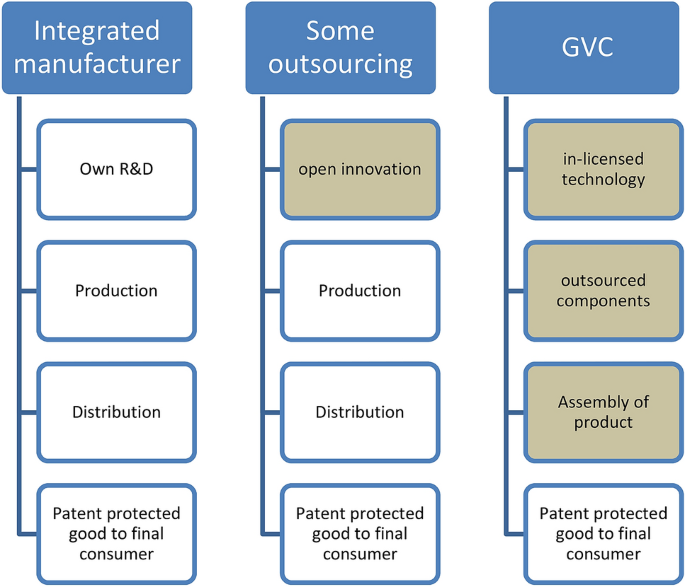

One important consequence of the new possibilities opened up by GVCs is that attention has shifted from market share arguments (based on the economic efficiency of IP policies) toward property-based arguments that highlight the role of IP in facilitating technology trade and the emergence of disintegrated, specialized technology markets (Spulber, 2021; Barnett, 2011; Arora, Fosfuri & Gambardella, 2001; Athreye, 1997). The greater is the use of specialized markets, the greater the need for IP to enable transactions across them. This is shown in Figure 2, adapted from Barnett (2011), which illustrates the different IP requirements of the integrated and disintegrated industrial organization models. The first model in Figure 2 represents the classical case of R&D-based innovation to produce a technology product (as in the case of big pharma). But the next two models represent different realities of subcontracting and vertically disintegrated supply chain models, with the second and the third being representations of sectors like Semiconductors or the new Biopharma. What is interesting is the more IP-intensive nature of the second and third models shown by the shaded boxes, which involve IP-based technology transfer activities. The more points at which IP transactions occur as technology is handed over for further processing to create the final product, the more patent-intensive is the final product. Having patents protecting these stages reduces transactions costs. The higher the division of labour in R&D, the more the scope for such IP transactions. However, this IP is for the most part protecting very small market shares as each stage involves a number of different operators.

ICTs, due to the higher use of patents in more fragmented value chains, increased the scope for TRIPS-like provisions. This is the case even in those sectors like telecommunications where it is not immediately obvious that patents are always the most effective means for protection as technology is changing so rapidly. Widespread patent ownership created other issues – such as the difficulty of new innovations in the presence of fragmented patent ownership (patent thickets) and blockage to innovation that is cumulative. In these instances, sectors have come up with their own institutional innovations such as patent pooling to permit cross –licensing of fragmented patent ownership into a single contract in ICT and the use of Fair, Reasonable, and Non-discriminatory licensing of essential patents (FRAND) to allow scaled up manufacturing in telecommunications. The effect of these institutional innovations in the governance of IP on globalization of R&D and production is sadly an understudied but important subject.

Although Figure 2 does not distinguish between domestic and foreign operations, we can speculate that MNEs’ strategic choices also influenced the effects and trajectories of IP policies in different countries (Bessen & Meurer, 2008). The global fragmentation of value chains is associated with multidirectional flows of information and knowledge across the entities involved in the international network of MNEs (Markus, Sia, & Soh, 2012) and weak IPR protection increases the risk of information leakage and misappropriation (e.g., Martinez-Noya & Garcia-Canal, 2011). Successful GVC integration requires a dense circulation of information flows to communicate specifications, standards and technical know-how in addition to costs and other items (Gereffi, Humphrey, & Sturgeon, 2005). Within this context, lead firms need to weigh the advantages of disaggregating the production process and the cost reduction this can bring against the risk of losing control over some of their proprietary intangible assets. Thus, lead firms engaged in GVC trade are interested in stricter IPRs in trade agreements to contain the risk of IP appropriation resulting from the international fragmentation of production. However, in order to circumvent the difficulty of using formal IP protection channels and to find other ways to enforce IPRs without limiting the scope of GVC activity, other mechanisms for the management of IP are increasingly emerging, mainly based on the attempt to move beyond legal procedures. Strategies such as a finer slicing of the processes (Gooris & Peters, 2016), or a sort of holistic approach using Corporate Social Responsibility to enforce stricter IPR standards along the chains (Gillai, Rammohan, & Lee, 2014), or the actions aiming at fostering “a culture of IP protection and compliance” throughout the global supply chain are all becoming mainstream (WIPO, 2017).

On the flip side, many middle-income countries that aspired to move up the technological ladder and build their own domestic capabilities, could see a new path to growth through participation in GVCs if they were willing to embrace the tougher IP demands in TRIPS. For example, as MNEs became willing to locate their production in different countries, industrialists in these countries (hoping to become part of a global value chain) were also willing to conform to the IP standards required by the MNE – often with more stringent enforcement (Brandl et al., 2019). In fact, the tightening of IP regulations and the deeper integration between countries through regulatory standards convergence (Rodrik, 2018) goes in parallel with the expansion of GVC trade (Timmer et al., 2014). This has led authors like Chang (2002) to protest that the stronger and better institutions for development demanded of developing countries today was not fair but an attempt to “kick away the ladder” to prevent developing countries from joining the elite club of developed nations. However, China’s rise shows us that if the government/firms were prepared to make the R&D investments, then strong IP need not be a deterrent to technological growth in lower income countries. Indeed, China’s rapid growth today and the effect of its prosperity on the growth of other Middle and Low-income countries is testament to the success of such strategies, although as Gomory and Baumol (2001) predict, such a strategy can create conflicts when the incumbent countries feel that their market share is threatened.

The growing role of intangible assets (technology, design and branding) in production is increasingly reflected in the growing share of intangible assets in the value of final products in international trade (Durand & Milberg, 2020; WIPO, 2017; Timmer et al., 2016). Hsieh and Rossi-Hansberg (2020) attribute this to a second industrial revolution in services sectors due to which productivity in services has been raised by ICTs in a manner similar to what machines and mechanical engineering did during the first industrial revolution. Furthermore, lead firms in GVCs are increasingly focussing on the intangibles, while outsourcing the tangibles to their partners in Middle and Low-income countries. As a consequence, more protection of intangibles is being demanded under the ambit of TRIPS such as protection for data, trademarks and copyrights. Sectors that have greater intangible capital – whether because of technological knowledge or consumer goodwill (brands) – are also able to earn more by judiciously choosing their location strategies.

There is a growing recognition in the IB literature that institutions are not always exogenous and instead co-evolve with firms: as the behaviour of firms starts changing, institutions start adapting as well (Athreye, 2020; Cantwell, Dunning, & Lundan, 2010; Peng et al., 2017). However, the imposition of TRIPS and the acceptance of seemingly stringent agreements and the shift to stronger IP for Middle and Low-income countries was exogenously driven. Once the status quo changed and the new institutions were in place, actors did change their strategies and new political possibilities emerged (as was discussed earlier).

The papers in this special issue in one way or another describe the various strategies used to drive policy in the national implementation stage of the TRIPS agreement. One way in which a more nuanced use of harmonised IPR could emerge is through the drafting of more detailed IP chapters in Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs) between countries. The paper by Christoph Mödlhamer argues that the innovative capacity of states that are members of a preferential agreement shapes demand for IPRs in the PTA. Innovative economies that rely on IP generation favour IPRs because IP-reliant industries press for IPR inclusion when governments negotiate PTAs with less innovative economies. By contrast, PTAs between non-innovators remain sparse in IPR provisions because few industries on either side demand IPR. Analyzing novel data on IPR provisions in 495 PTAs signed between 1988 and 2018, he shows that heterogeneity in PTA members’ innovativeness indeed increases the inclusion of IPR clauses in PTAs. His findings help to understand preferences towards IPRs in PTA negotiations and shed light on reasons for varying numbers of IPR inclusions, while offering a refinement of the conventional wisdom that adds to our understanding of PTA design.

In general, these findings on IP chapters of PTAs are consistent with Gamso and Grosse (2020). They find that deep PTAs with provisions such as investor-state dispute settlement mechanisms and property rights protections provide signals that are especially important to investors in countries where property rights are weak, as the extra protections provided by a deeper agreement can substitute for those that are missing at the domestic level. Empirically, they find that PTA depth is positively associated with FDI between member countries, but the association weakens as property rights laws in host countries increase in strength. Thus, they conclude that governments can attract higher levels of FDI through comprehensive trade agreements, as opposed to shallow PTAs, when domestic policies are not sufficient. However, shallow agreements suffice where domestic policy already protects property rights.

For many countries, another obvious way to prioritize national interest is to weaken the ‘national treatment’ principle in enforcement. A growing body of work has demonstrated anti-foreign bias in patent grants by offices around the world such as the JPO (Helfgott, 1990), EPO (Kotabe, 1992) and SIPO (Brander, Cui & Vertinsky, 2017). Though most of this evidence shows correlation rather than causation, if true it is a repudiation of the ‘national treatment’ principle, which as we noted earlier was a central pillar of the Paris Convention and TRIPS.

The paper by Rassenfosse and Hosseini, using data for the USPTO, shows that inventions of foreign origin are about ten percentage points less likely to be granted a patent than domestic inventions, which suggests discrimination against foreigners. Why does such discrimination exist? They distinguish between intentional and unintentional discrimination. Intentional discrimination relates to disparate treatment of a specific group of applicants, whereas unintentional discrimination arises when policies, practices, and rules have disparate impacts on a specific group of applicants. Their analysis shows that the bias against foreigners is largely the result of unintentional discrimination and can be explained by differences in patent agents used by foreigners and locals, the financial resources of the applicants, and the level of effort that applicants put into the prosecution process. Thus, the story they tell is about disparate impact (due to better financial resources) rather than disparate treatment.

The paper by Petit, van Pottelsberghe de la Potterie and Gimeno-Fabra disagrees with the results presented by Rassenfosse and Hosseini and argues that tests of the national treatment argument should be conducted not on grant rates (which may be influenced by more adverse market conditions facing the foreign applicant) but on the examination process. The examination process is defined as the work carried out by the patent examination office (to assess if an application fulfils the legal patentability conditions), which is assumed to be (mostly) independent from economic forces. Testing for national bias within the examination process relies on the fact that patent offices are legally required to justify each decision they publish through concrete and transparent evidence. As a result, discriminatory behaviours from patent offices should show up in the way applications are processed. Using this alternative empirical approach to test for national bias at the EPO, the JPO, and the USPTO, and through a unique database that quantifies the key patent examination processes and find no evidence of national bias throughout the work of three patent offices (WIPO, EPO and USPTO). 15

The paper by Ramani and Urias reviews the use of the much-publicized TRIPS flexibility – compulsory licensing for public health – in middle and low-income countries. Compulsory licensing is considered an important policy instrument to make medicines affordable in countries where a pharmaceutical industry does not exist or where stronger TRIPS provisions on product patents are likely to increase the prices of medicines placing then out of the reach of a large segment of the population in many low and middle income countries. Based on a systematic review of the existing evidence on the impact of compulsory licensing on drug prices, Ramani and Urias identify 24 instances of compulsory licensing in 8 countries – which is a very limited use of this much touted flexibility. They attribute this limited use to the very restrictive scope for the use of compulsory licensing in the TRIPS provisions.

Comparing pre- and post-compulsory licensing prices, their paper finds that a compulsory licensing event is likely to reduce the price of a patented drug, although public knowledge of the extent of price drop is poor. Further, they find compulsory licensing procurement from the international market is likely to be more effective in reducing drug prices than contracts to local companies. Interestingly, their findings are reconfirmed in the race to improve access to the antiviral medication Remdesivir for hospitalized COVID-19 patients, based on information that is publicly available. Clearly, the future incidence and impact of compulsory licensing will depend on further possible procedural refinements to ease its implementation, the development of technological and manufacturing capabilities in developing countries, and the importance of biologics among life-saving drugs. COVID-19 could prove a pivotal moment in redefining this flexibility and enabling its wider use.

Finally, Abinader’s in-depth analysis of pharmaceutical patenting in the Dominican Republic, a country that does not ordinarily receive much attention in the literature on IP, sheds light on what conformity with TRIPS looks like in practice. The paper allows us to observe patent prosecution in a developing country where substantive examination is new. The finding of low grant rates, not just for more questionable “secondary” patents but also for “primary” patents covering active ingredients suggests that, TRIPS-driven harmonization notwithstanding, domestic politics and state institutions continue to cast a substantial influence over de facto levels of patent protection.

Although the papers in this issue do not cover all aspects of international business since TRIPS, we hope some of the issues noted in this Introduction and in the included papers will create a rich menu of future options for research on TRIPS and patent policy by IB scholars.